This essay was originally published by No Agency. Like life, it contains explicit content.

I used to go on the internet, and when I did I would post things, and people would reply, and I would tell myself stories about these people, and sometimes I would be right.

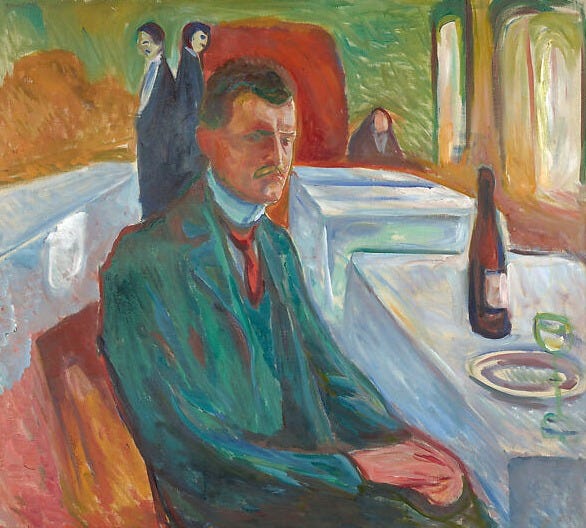

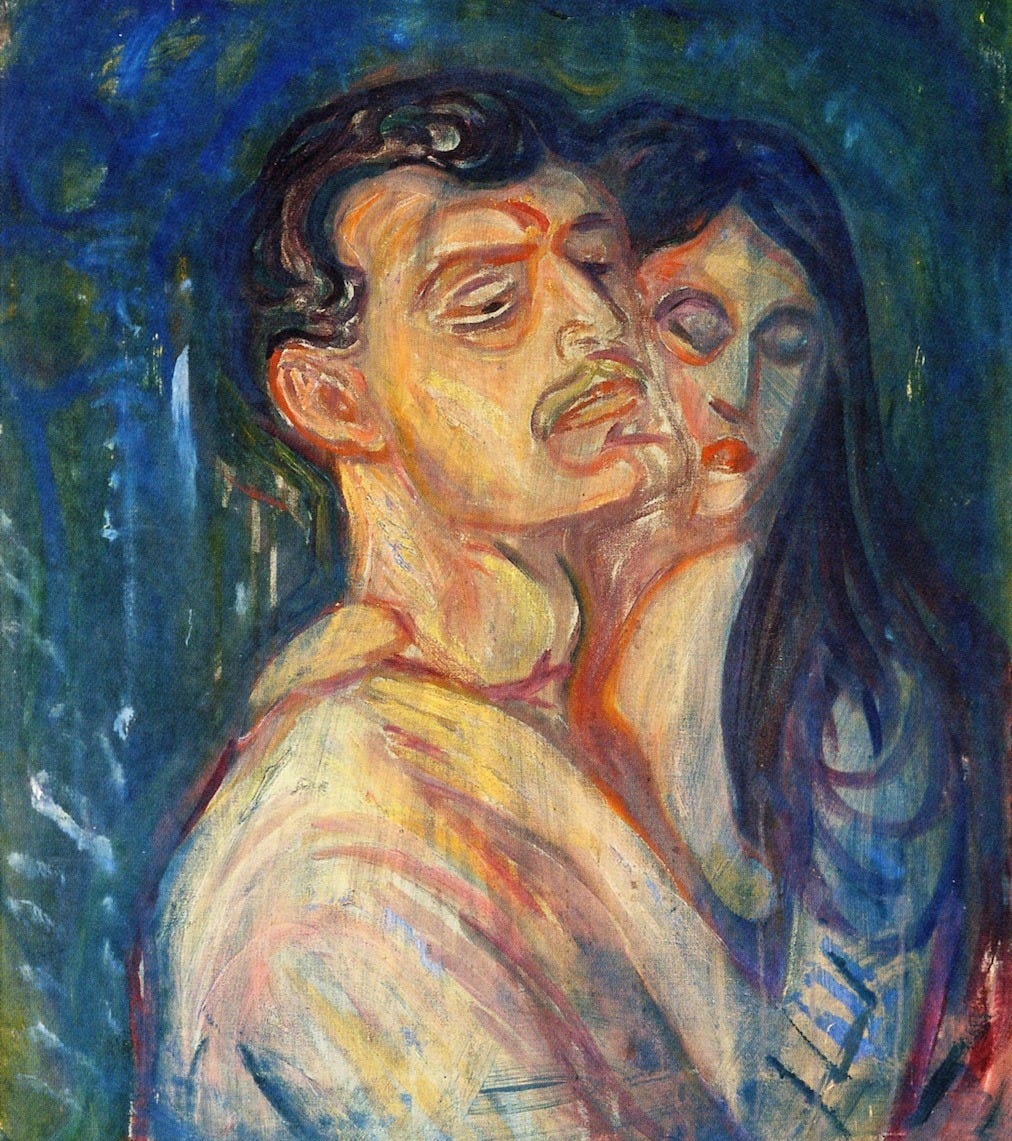

His profile photo was a painting by my favorite artist. Because both the painter and the subject were attractive men, I assumed that this also applied to the person who had chosen this image. His name was Sam. He sent me a message.

I was new to the city, attending events every night, learning people’s names and histories, what they wrote, who they fucked, who would remember me the next night and who would forget me the next morning. According to Sam’s list of followers, we knew the same people. It wasn’t the endorsement that mattered; it was the evidence that he was real.

If I doubted his existence, it was because things were going so well. One message led to an exchange, and then another exchange, until the exchanges were no longer distinct, becoming an ongoing dialogue interrupted only by sleep and Sam’s sudden absences. “Gotta run,” he would type in the middle of a thought, disappearing before I could say goodbye. I never knew where he went nor when he would return. But I was always ready.

Two weeks into our conversation, Sam posted an event flyer to his feed. It was for someone else’s reading, but I figured this meant he would be there. I bought two tickets and forced a friend to come along.

“How will you recognize him?” she asked.

”I won’t,” I said. “He’ll have to find me.”

At the venue, I circulated continuously to increase my odds of being spotted. (I did this without the friend, who was petite and blonde.) Anyone could’ve been Sam. Each moment arrived with immense potential, and left with nothing to show for it. No one approached. The reading ended and I stood by the exit, watching the crowd leave along with my hopes.

Sam did things for me, from afar. He connected me to a magazine editor. He set me up with design gigs. He bought one of my drawings.

“Should I ship it?” I asked. The subject of our in-person meeting was one he had deftly side-stepped in the past.

“I’m not in New York for the next few weeks,” he said. “But let’s do a hand-off when I’m back.”

This was it! I told my friends. I read the books he’d recommended. I moved with new energy, spoke with new levity. I had happiness to spare. I cast it around like rice at a wedding. I still could not picture his face.

“There are no photos of you online,” I wrote.

“I’m a private person.”

“Can you at least tell me where you are?”

“Minnesota,” he said. I could sense his hesitation in the pause between messages. “My wife and I moved here from Brooklyn.”

It was too late for me to turn back. I cared too much.

“I’m working on a short story,” he wrote a few days before flying to New York for what would turn out to be a brief business trip. “It’s about you.”

“Can I read it?”

“Not yet.” Sam enjoyed making me wait, withholding things until I begged. I was starting to wonder if his absences were not in fact necessary but rather engineered to increase his desirability and my desperation.

“Send it before you get here,” I said.

He did send something, but it wasn’t the story. It was an essay about working parents, artists balancing the demands of childcare and precarious freelance careers.

“Makes me grateful I don’t have kids,” I typed, unsure of what he wanted. Was I supposed to give feedback?

“I have a daughter,” he replied. “She’s three months old.”

We met at a bar. He looked exactly as I expected, which was shocking. I ordered sparkling water. He ordered beer. Then whisky. Then more whisky.

“Just out of curiosity,” I asked once I was sure he was drunk. “What’s with all those sudden departures? You’re always rushing off.”

“Oh,” he said, rotating his glass on the table, not looking up. “I have to check on my daughter whenever she wakes up.”

We talked until four a.m. That’s how long it took me to decide.

“I can’t come back with you,” I said finally. He was flying home the next morning. It didn’t matter whether I wanted to sleep with him. I wanted more, which was the same as wanting nothing.

He was gracious as he left. “I’ll send you the story,” he said, and I watched through the window as he tripped on a paving stone. He was so drunk, he fell to his knees.

The story was titled, “I Fucked August Lamm in My Head.” The opening was a sort of command: “He knew that she would forgive his imagination anything.”

The protagonist shows up at my painting studio and leads me to the bathroom, where he bends me over the sink and fingers me from behind. In the mirror, I am “faceless, a body without a face.” I am taller than he anticipated. “Had she been the correct height, he would have been able to make eye contact with her reflection.”

The limitations of the bathroom setting continue to play a role in the story. “It was not lost on either of them that the toilet was there beside them. She had been pissing and shitting there with the same cunt and asshole that he was now filling up.”

He wonders whether I am on birth control, then decides that he cannot “trust [me] to give an honest answer.” He hesitates between my vagina and butthole, then decides on the former, pulling out almost immediately to cum on my thigh. A thread of jizz “hangs quiveringly over the back of [my] girlish right knee.” As someone self-conscious about my knees, I treasured this description.

The story spans a decades-long affair. Sam remains married; I remain single. “As her star rose, she had other friends and other, more important lovers. But always she kept a corner of her mind for him.” Alas, my declining health eventually puts a damper on his visits. Now there are medications to administer, bedpans to change. Pain is all I am capable of feeling; Sam fucks me all the same. “Good sex consisted in him taking, confidently, what she had given him to understand was his to take. She never gave much sign of the pleasure, if any, she felt in this.”

Finally, when the pain becomes too much, he helps me commit assisted suicide. (I apparently do not have any friends or family.) In a dramatic flourish, he sets my death in the hospital where I was born. “He signed on the forms and agreed to be present in the room in Yale-New Haven Hospital, this being some years in the future and Connecticut law having changed.”

Reflecting on my death, he feels at peace. “Yes, he had killed her, but the law, in whatever wisdom, smiled on it; he hadn't done anything wrong. But there were other spirits, other furies—his wife, maybe—that he would have to repay.”

I cried as I read it. Was this how men saw me? Just a lonely cum receptacle to be killed off once my enthusiasm waned? “He hadn’t done anything wrong.” I disagreed.

It took me all day to compose a reply. Meanwhile, Sam’s messages grew more and more concerned. For once, he was the one waiting. I wanted to send something that would humiliate him, put him in his place. I wanted to threaten him, expose him, ruin his life. “The scene where I became fully disabled was funny,” I wrote finally. “Bedpans lol fuck me.”

In 4,000 words, he didn’t give me a single line of dialogue. “Autofiction is safe sex,” he wrote in the opening paragraph. Maybe so. But the story I’m telling isn’t fiction. This one is dangerous. This one is real.

Halfway through the essay I literally went "Oh. Oh no :("

I had felt uneasy about him throughout the story but gradually felt more and more reassured like "oh maybe this internet stranger is normal and nice after all" and then NOPE, creepy adulterous dude writing smut about a real, non consenting person. I don't know what bad thing I was expecting but I can't say that was it. Total whiplash.

Great piece, August. I felt so many emotions in such quick succession. But I'm sorry you went through this gross and demeaning experience and wasted time on this person. I hope his wife sees this and his daughter never does.

Mic drop. Excellent essay