I keep forgetting what city I’m in. Not just when I wake up, but throughout the day. I’ll see a certain configuration of brick buildings near an intersection in Brooklyn, and I’ll think, The 24 hour bagel shop is around here. But the bagel shop is in London. I’ll walk through a park and think, What if I run into my ex? But the ex lives in Paris. I’ll think to hang out with foreign friends. I’ll forget that local friends are right around the corner. I’ll forget whether Europe is asleep, and whether I’m awake.

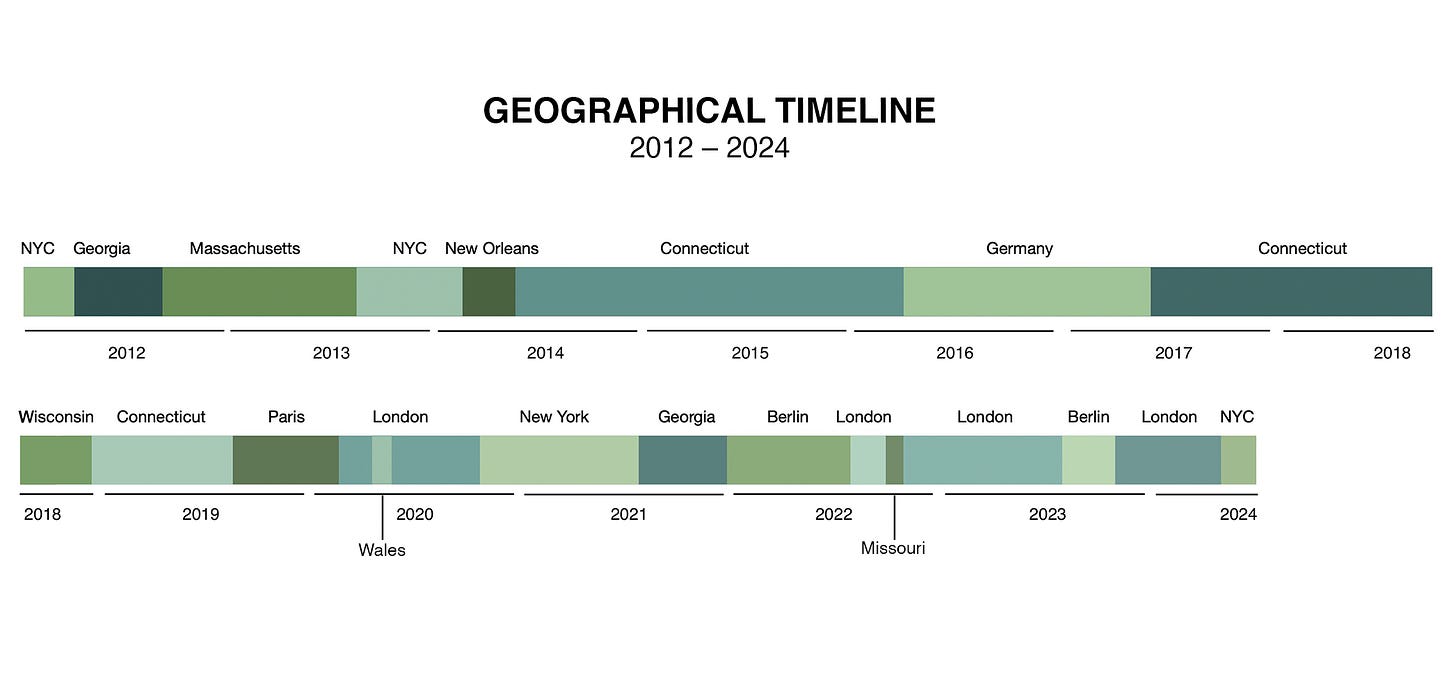

For a long time, I’ve wanted to make a timeline of my geographical whereabouts since I left home at 16. I’ve also wanted to paint, from old photos, every apartment I’ve ever lived in. But that would be too many apartments. One year, I moved a dozen times: four countries, six cities. I couldn’t fit it all in the chart. I couldn’t take everything with me.

When you move that much, you accumulate the same items over and over again—three bikes (London, Berlin, Missouri), three guitars (London, Berlin, Connecticut), many shelves of books (London, Berlin, Connecticut, Missouri, Atlanta, New York). You buy soap and sunscreen and socks. You buy what you need for work: desk, chair, keyboard, mouse, easel, paint. The paint is expensive. You hoard papers—receipts, letters, unpaid bills. You forget to pay bills. You forget to cancel the wifi at your old flat. You depart halfway through your gym membership. Every move is a gamble. You lose money. You lose friends.

It’s interesting to take stock of the objects that always travel with me, the ones I never leave behind. They are: laptop (for obvious reasons), tablet (illustration commissions), white noise machine (insomnia), hairbrush (hard to find a good one), journal (I have thoughts), paint-covered jeans (can’t ruin my other clothes).

The other constant is my work. Wherever I go, my task remains the same: a combination of writing, painting, sending emails, and promoting myself on the internet. Wherever I go, you will always find me on the internet.

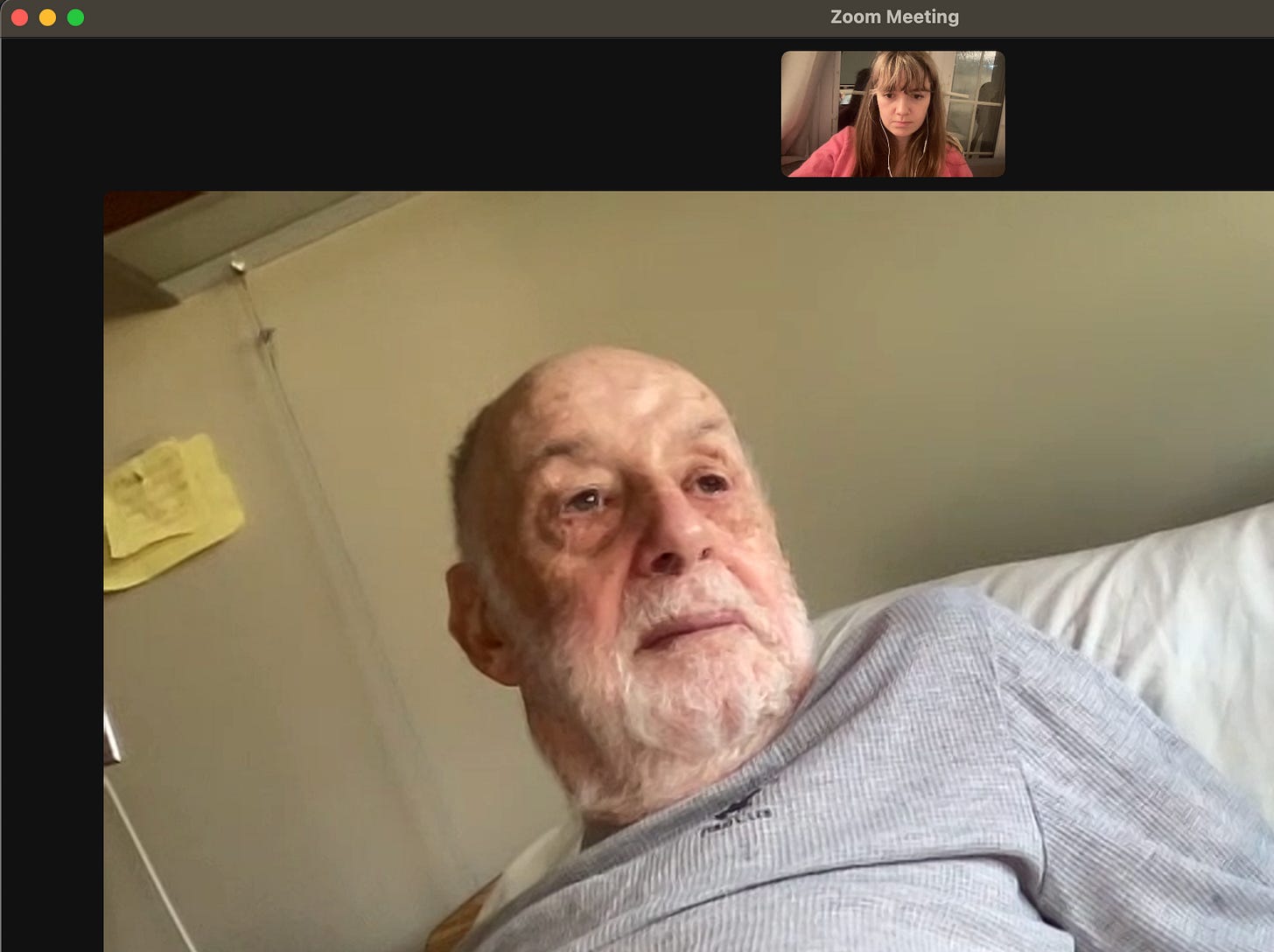

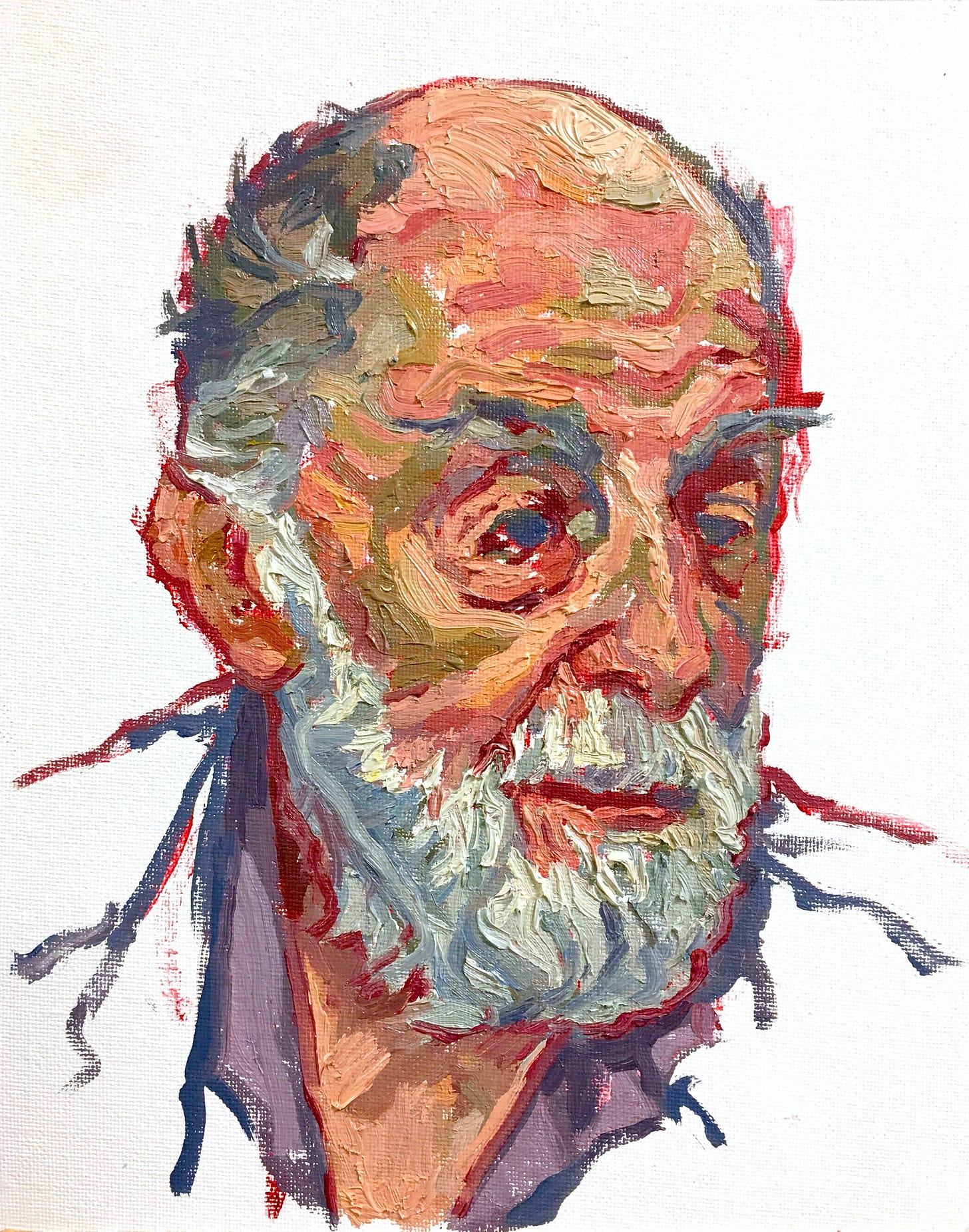

Where are you now? people ask me all the time, via online comments and messages. It’s the same question I ask my dad. Where are you now? A few hours after he died last month, I realized that for the first time since his birth, he no longer had a location. He was just as much in my apartment as in the morgue, as much in Connecticut as in Cambodia, on Earth as on Mars. It was kind of exciting! He was anywhere, everywhere! But really, he was nowhere.

Since my dad died, I’ve been talking to a man on the internet. We’ve never met. He lives far enough away that our physical forms are irrelevant. I don’t really know why we talk. Why does anyone talk? Sometimes we’ll message back and forth for a few hours, and then he’ll go back to his life, and I’ll go to my mirror and stand there for a minute, watching my eyes blink, thinking, This is how you are spending your life. It is clear to me, as soon as I close my laptop, that for the past few hours I have done nothing at all. But try telling me that when I’m partway through a conversation. Try telling me it’s nothing.

If I can invoke the presence of this stranger, if I can believe he is real, then why can’t I invoke the dead? If I can talk to this stranger wherever I go—a coffee shop, a friend’s apartment, a commuter train—then why can’t I talk to the dead?

I know why, of course: because to speak to my father is to admit that he’s dead. He’s not in the nursing home or his apartment. He’s not out to eat, or watching a movie, or doing physical therapy. There is nothing physical about him anymore. Last week, I scooped his ashes into a grave. Some of them got blown across the grass, refusing to stay put.

It is easier to avoid talking to my father than to admit that I no longer have a choice. It is easier to go somewhere else, packing the same hairbrush I owned when he was alive, than to stay in my hometown without him. It is easier to wait for a message than a sign. It is easier to send a message than a prayer.

It is easier to keep talking than to stop. It is impossible to begin. Does that make sense?

Hi dad, it’s me. I’ll be in touch someday. For now, it’s easier to conjure someone else’s ghost.

Your timing, like your art, is impeccable. I just got back a few days ago from paying my respects to the portfolio of my late mentor/father figure (also 1st trip anywhere since Covid hit.) Overwhelmed by the suddenness of his death last year, his partner completely spaced letting me know, so I found out when I called a few months ago to wish him happy birthday, nearly a year after he had passed.

So, similarly, I felt a huge disturbance in the Force when flying into a Minneapolis that no longer had Jack in it. Nothing was moored to anything, especially my memories of the years we worked together.

I was fine with the way the visit was going, with a lot of grief unpacked, until faced with picking a memento from over six decades of prodigious output. He created as constantly and exquisitely as you do, & I see so much of what I admired most in him in you. (This does not mean you should start smoking cigars, though.)

So — again — thank you for this gift. Catharsis is contagious, and no mask can stand against it. ❤️

This is so beautifully written. I just read a book recently dealing with the same thing. Called Telephone of the Tree, if you’re so inclined.

I’d love to see you be able to paint all of those places somehow…maybe someday. You still have time