Note: The following is the eulogy I delivered at my father’s funeral last week.

I’ve imagined giving this eulogy hundreds of times. Over the past decade, I’ve devoted one in three plane rides, one in five showers to the mental writing of this speech. The challenge was capturing the slippery, double-edged memory of a parent at once larger than life and too small to see. I've imagined this eulogy so often that it has occasionally folded in on itself, and I’ve imagined telling you all, I’ve imagined giving this eulogy so many times that I’ve even imagined telling you all I’ve imagined it, and so on, until the water in the shower went cold. Sometimes I would come up with a line so perfect, I almost wished for the chance to use it. But I never wrote anything down. To write it down would have been to accept that this moment would actually come, that one day I would face the bare logistics of death, the condensing of a beloved person into paper, stone, words. I wasn’t ready to write it. I wasn’t ready to need to.

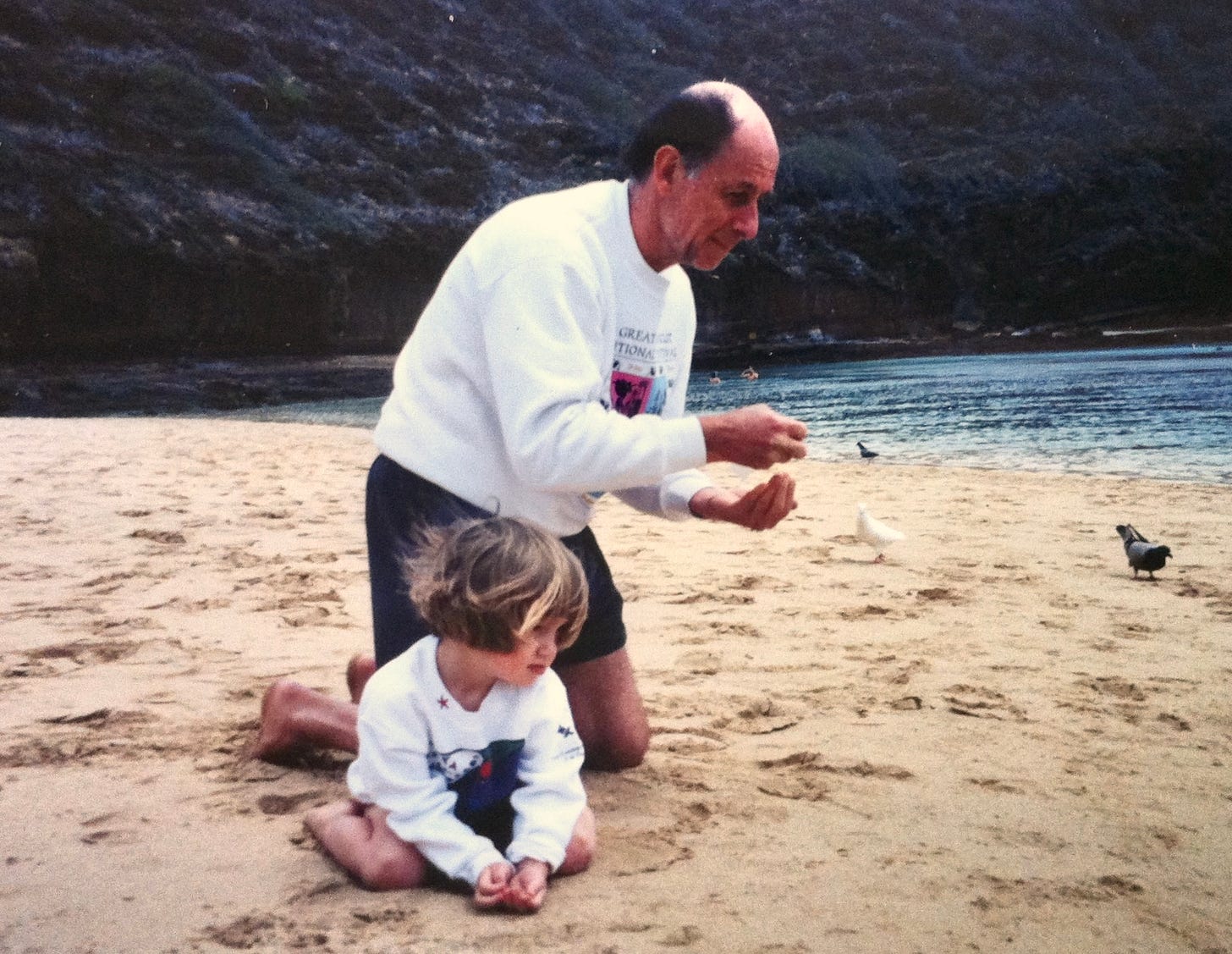

I lived in terror of my father’s death, constantly on high alert. An unheard voicemail was as good as a death notice. I couldn’t open my email without bracing myself bad news. Even now, in the aftermath of his death, I still sometimes see a missed call and think, Oh no, did he die? The feeling that follows is somewhere between relief and despair. My father was six decades older than me. We had less than three decades together, making me one of the people who knew him least. But only by one metric.

In every child’s life, there is the space for a parent, regardless of what fills this space, love or its opposites. At times in my life, it was convenient for me to believe that the space was empty, that I was as good as fatherless. This was convenient for two reasons. First, it spared me the complication of looking into that space and reckoning with what was or was not there. And second, because an absence was easier to explain than a complicated presence. I wasn’t raised by my father, I would tell people. I didn’t live with him. This was true, yet it falsely equated proximity with influence. I knew full well that a personality like my father’s could transcend geography, that he was always with me, despite rarely being there. On the day he died, I stood uncomfortably across the room from his body, feeling no urge to approach him, to touch him while I still had the chance. He was not in his body. I had never found him there. If I wanted to find him, I would have to look where I’d always found him: within myself.

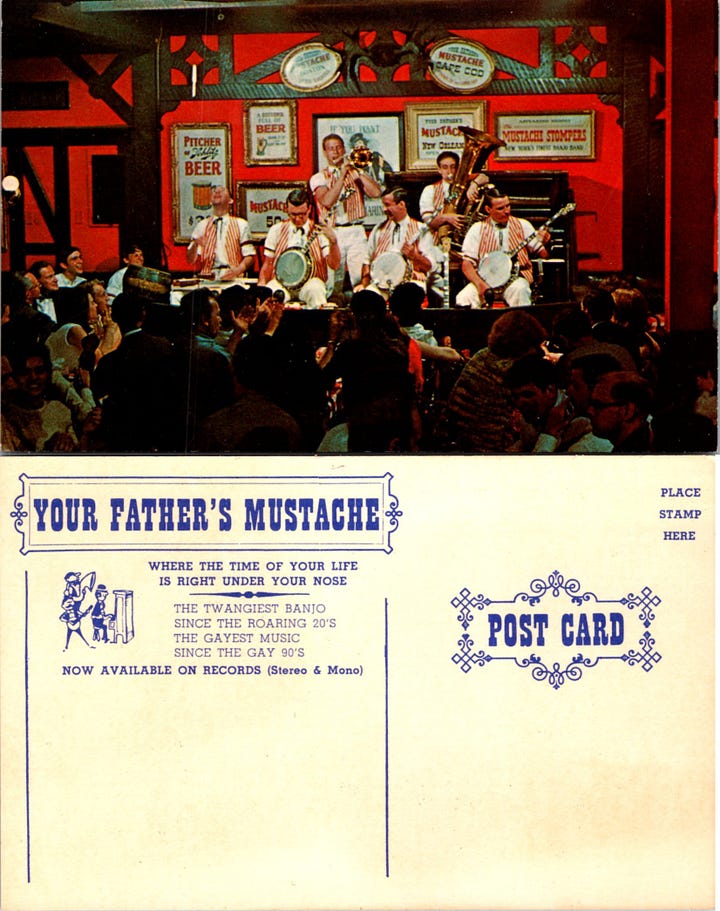

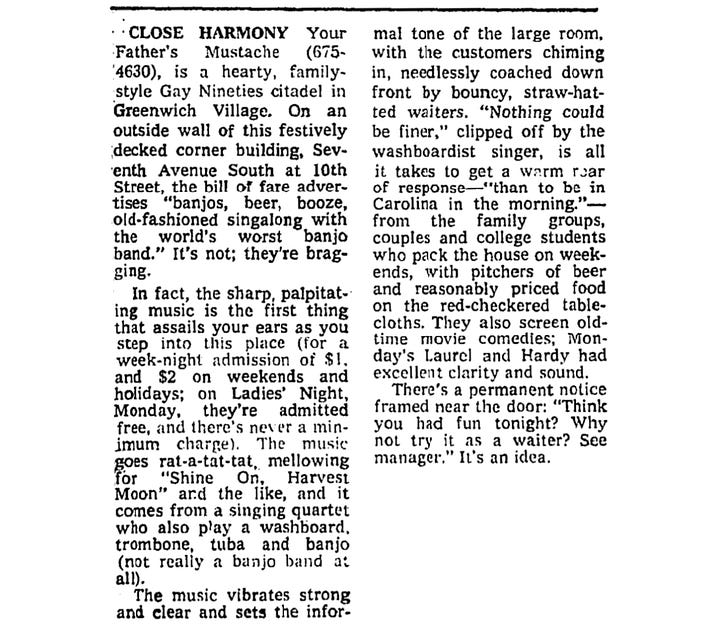

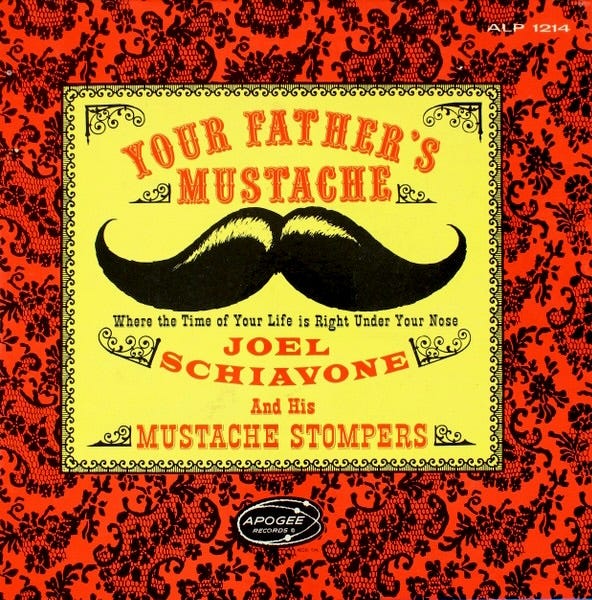

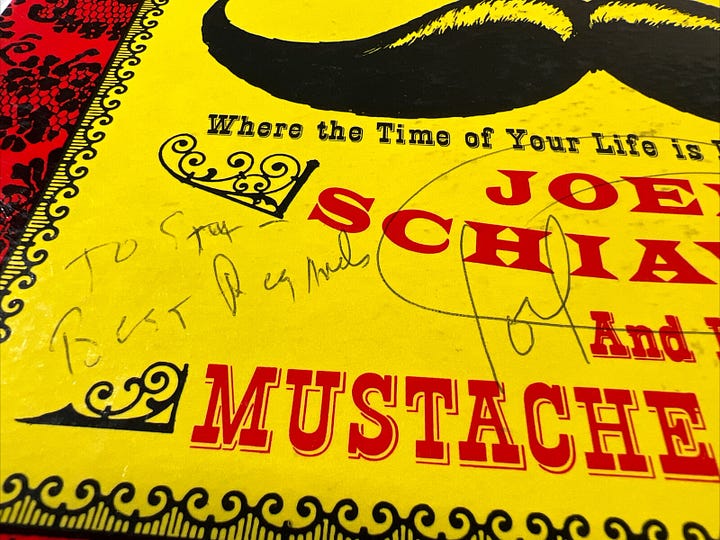

My father was a born performer. He loved attention, but unlike most attention-seekers, he earned it. He was a generous onstage. He would captivate an audience, and the audience would stay captivated, for years, decades, a lifetime. It wasn’t just his charisma. It was practice and preparation. It was costumes and venues and programs and signs. It was mailing lists. It was stacks of songbooks, spiral bound, containing every song written before 1950—the year after which, to my father’s mind, no significant further developments in music were made. There were printed setlists with annotations written in his trademark illegible script, those jagged ranges of misshapen capitals that rendered checks worthless and mail undeliverable. There were late nights shut up in his study, just him and the banjo, rehearsing the set over and over until each song led seamlessly into the next. He worked hard to entertain, and it is a testament to this work that even in his later years, when the songs were tired, the lyrics inaudible, the chords half-forgotten, the venue a Mexican restaurant in the suburbs—even then the audience showed up, and went home feeling as if they had witnessed something remarkable.

Had my father gotten his way, this funeral would’ve been held long before he died. He would’ve been here to witness it, or more likely to run the show. And while I like to think we’ve done an alright job organizing, we all know it would’ve been better if he’d been in charge. In addition to the music and speeches there would’ve been surprises, stunts and gags, semi-nudity. If my father were standing up here right now, he would certainly not be reading from a sheet of paper. He would be looking out at the audience, making each and every one of you feel like the only person in the room. That was his gift. He would be trying to suppress a smile at the thought of whatever was up his sleeve, whatever was coming next, knowing how delighted you’d be once you figured it out.

I’ve lived abroad for most of my adult life. I visited home twice a year. As my father got sicker, he wanted more of me than I could give. He knew he didn’t have the right to ask. After all, where had he been when I’d been sick? When had he ever sat at my bedside? I tried to foster a resentment, to lean into the bitterness, but I didn’t really feel it. Hating my father for failing to parent me would’ve been like hating a cow for failing to lay eggs: parenting was never his calling.

When I say parenting, I mean it in the literal sense: the changing of diapers, the packing of lunches and scheduling of doctor’s appointments. In my father’s case, the definition is too narrow. Because I do feel shaped by him, nurtured indirectly, from a distance, theoretically, the way you can be shaped by a book, an idea, a foreign culture. You don’t need to live alongside these things to appreciate them. You just need to know that they exist.

My father believed I could do anything. When I wanted to start a business, he gave me a copy of The Harvard Business Review and How to Win Friends and Influence People. It didn’t matter that I was 12. When I wanted to learn German, he sent me to Germany. It didn’t matter that I was 14 and needed a flight attendant to chaperone me through the airport. When I wanted to become an artist, rendering my expensive academic degree all but useless, he said why the hell not? When I wanted to move to London for no justifiable reason, he said I was doing exactly the right thing. When I wanted to write a book, he said, When can I read it?

But his belief in me did not stem from the fact that I was his daughter. Any objective brilliance I may have possessed was irrelevant. My father believed in everyone. To his mind, the average person was living within false mental boundaries that could, with the right combination of confidence and determination, be cast off in favor of a more fulfilling, if unorthodox, existence. Of course, this was easy to say if you went to Yale and Harvard and received a multi-million dollar inheritance. But none of that applies to me. I inherited no money. I inherited nothing, except the feeling that I could have everything.

Like my father, I get a lot of crazy ideas, and like him I pursue most of them. Often, they lead to disaster. I move from country to country, project to project, leaving half-formed thoughts in my wake. Like my father, when I win or lose, I do it on a large scale. The stakes are high. But what a fun life. What a mess of a life. My father was a disaster. He loved the wrong people too much, and the right people too little. He preferred the idea of things to the details. He was a stubborn optimist with no patience for doubts. He pushed relentlessly forward, never casting a backward glance. He wanted more, but at whose expense?

When things fall apart in my own life, when I find myself broke or broken, I sometimes wonder whether it’s time to quit the adventure, to pack it up and go home and embark on a more modest life, one with lower stakes, one that makes sense on paper, one easily explainable to strangers at parties. I want to be a person who can answer simple questions simply. Where do you live? What’s your job? But then again, aren’t there enough people like that? And thank god for those people, the ones who build and maintain the theater of life so people like my dad can get up on stage and put on a show and eventually burn the whole place down for the insurance money. Thank god for the responsible parents, the reliable partners, the sound investors, the diligent workers, the people who show up day in and day out, who just want a simple normal life, or who have no other choice. These are the people who keep the world turning. Where would we be without them? And equally, thank god for the occasional break in the chain, the spark of mischief in the ranks, the rare person who won’t fit neatly into one category or another: musician or politician, husband or bachelor, philanthropist or con man, father or that guy I had dinner with once a month at Bertucci’s. My father taught me that you can be any number of things, that you can fail at most of them, and it will still count for something. It will still be a life. It will be more than a life. It will be a phenomenon.

This was what I needed from a father. I needed to grow up in the orbit of someone who lived by his own rules. I was such a weird kid, out of place at school and at birthday parties. I never would’ve survived the workforce. If I was going to survive, I needed an alternative path. I needed that far more than I needed homework help or a ride to soccer practice, more even than I needed love and care. I may be emotionally damaged as a result, but that pain is nothing compared to what I would have suffered if forced to live a regular life.

In the months since my father died, I have stopped imagining this eulogy. I put off writing it until the day before the funeral. I realize now that all those brainstorming sessions were an attempt to prepare for grief. Of course there is no preparation. This was always going to hurt. There is only so much that writing can do to help.

In a sense, it’s strange how much I miss him, how much I feel his absence. Two months is nowhere near the longest I’ve gone without seeing him. But the problem isn’t that I’ll never see him again. The problem is that he’ll never see us again. Will we ever appear as fascinating, as full of potential as we did through his eyes?

"[...] an absence was easier to explain than a complicated presence." Ding ding ding.

Really enjoyed reading this. My dad also passed away this year and I too had thought about his eulogy a million times. Well done.