Update: I have an essay in the New York Times today.

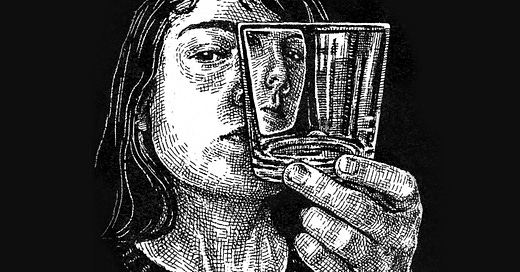

In my childhood home, alcohol was serious business. You didn’t drink for fun. There was no fun. You drank for survival. You drank for sleep, for sadness, for dinner. You drank in the morning, and in the middle of the night when you had a bad dream. But who were you kidding? All dreams were bad.

High school was a failure in every sense. I shaved my head and displayed enthusiasm for gym class. I tried getting into video games because that was how the other losers kept busy, but I failed, getting stuck on the lowest levels, having to google solutions at every turn. I also failed to make friends, failed most of my classes, and dropped out in junior year, never having attended a party, never having been kissed.

I was young for college, young in age and experience, still 16, having attained via standardized testing what is termed a “high school equivalency,” but which cannot replicate the crucial rites of passage — sequined dress, mortarboard, devirginization.

I started going to college parties without knowing what a party was. I had a bad time, and so did everyone who encountered me. My only social mode was earnest heart-to-heart. Strangers would abandon me for lighter dynamics — I’m just gonna grab another beer — and I would go back to my dorm to write in my journal, speckling the pages with tears, certain I had been born on the wrong planet.

I told all this to my mother when I visited home for break. “The problem is you’re not drinking,” she said simply. “Everyone else is drunk.” I went back to college and changed my ways.

In America, you can’t drink as a teen. You can’t drink in public, either. So you get drunk in the dorms before going out. You take shots, trying to gauge the proper amount based on your height and weight and how much you’ve eaten for dinner. Then you walk across campus to fraternity row.

My first experience of complete social integration was at Delta Kappa Epsilon on a Friday night. (The fraternity got shut down the following semester and, a decade later, has yet to reopen.) I was perfectly drunk, which is to say too drunk. I vaguely recall talking to a random guy about whatever, feeling totally unfussed about my internal world, my idiosyncrasies, and other such markers of humanity that tormented me during daylight hours. This was the only hour of my life in which I might accurately have been described as “chill.”

I got lost walking back to my dorm and ended up sitting alone on the lawn for an indeterminate amount of time, moving in and out of consciousness until some stranger directed me homeward. Then I lay down on my plastic mattress, holding tight to the corners so I wouldn’t fall off. I puked in my sleep and nearly died. I woke up and it was my birthday.

I stopped drinking after that — the smell of alcohol made me nauseous — and lost my friend group in the process. Social ties were cemented at pre-games, parties, brunchtime debriefs. The craziest thing happened. You won’t believe who was there. I got wasted. I’m so hungover now. While I could still attend the brunches, my presence was that of a chaperone, someone cloyingly virtuous and irrelevant. The invitations stopped. The group chats died out and were reborn without me. I coped in my own way, by writing sad songs, arranging internet dates with adult men from the local area, and obsessively tracking my food and water intake in a notebook I carried everywhere.

I dropped out of college. (I would eventually drop out of grad school, too; I’m not good with structure.) I moved to Berlin at age 20 with $200 in the bank. My plan was to play music on the street — I’d brought my banjo — but it turned out that Germans don’t tip well. In the land of social protection, begging is a sign of greed. I made about five euros per hour. It was unsustainable.

I was sleeping on the couches of strange men who were clearly hoping my resistance would falter after a few nights of hospitality. One man didn’t have a couch. I had to sleep in his bed. I woke up with his fingers inside me. The next day, I spent hours walking back and forth past the police station, looking up the German word for assault, then rape, unable to decide which it was, or whether any crime had been committed at all.

I found an under-the-table job at an ice cream shop, where I stole from the cash register to save up for my own place. I started renting a cheap room in the north of the city. I started dating, which in the adult realm seemed to require drinking. In Berlin, you could do so in public, which meant I didn’t have to pay bar prices. I discovered a brand of beer that cost a euro for a big bottle: Sternburg Export, or Sterni for short. It was the best liquid I’d ever tasted, the lovechild of seltzer and lapsang souchong. I still wasn’t eating much but I was drinking a bottle or two of Sterni per day.

Then I got a boyfriend and stopped drinking. He was my first boyfriend, and I loved him with all the pent-up force of my lonely teenage years. Every moment felt special. Alcohol was no longer required.

A year later, we broke up. I was so devastated that I checked myself into a psych ward. My roommate there was an alcoholic. Maybe she still is. I liked her a lot, but once you’ve seen an alcoholic at the point of institutionalization, it’s hard to enjoy being drunk again.

For a few years after that, I pretended to drink, just to keep up appearances. I accepted drinks at parties, taking tiny sips until I could retreat to the kitchen and dump it down the drain. When I did confess to sobriety, people would ask questions. Did you have a problem? Worse, they would get self-conscious. I should probably cut back, too, they would say, with no intention of doing so.

I didn’t grow up with my father, but ask anyone who knew him and they’ll tell you he was the life of the party. He ran an international chain of nightclubs and was known for cross-dressing, stripping, and surprising friends by turning up on a camel. And you know what? He never drank.

The reason (likely apocryphal) was that he once got so drunk in college that he fell out a window with his pants off. Who cares if it really happened? For the next seven decades, he stayed sober. He never concealed it, never apologized, never made excuses. He just ordered a ginger ale and got on with the night.

When he died last year, I decided to follow his lead and start being honest. So yeah, I don’t really drink. Who cares? Well, a lot of people do. Alcohol, it seems, is serious business. Guess I’ll leave it to the pros.

It’s great to meet another sober August! 🥰🥰🥰

Thank you for sharing your stories. I also don’t drink, and it was similarly a winding road of various experiences that led me to just not wanting it. I suspect it may become less culturally important in the US over the next couple decades, in Europe I’m not so sure.

Also just wanted to say that I honor your experiences of feeling so othered during your childhood and early adulthood. It is very challenging to have been born as anything different than the norm. People are afraid of what they don’t understand. You are clearly so talented (I am enamored with your drawing style, OMG) and a brilliant writer. Thank you for sharing your gifts. Congrats on the NYT article! I am really excited to follow your journey in Paris, I feel like it will probably be magical. Hugs xx